Swaida: Climatic Aspects and Economic Prospects – Review

Dr. Rada Maria Abou-Ammar

Introduction

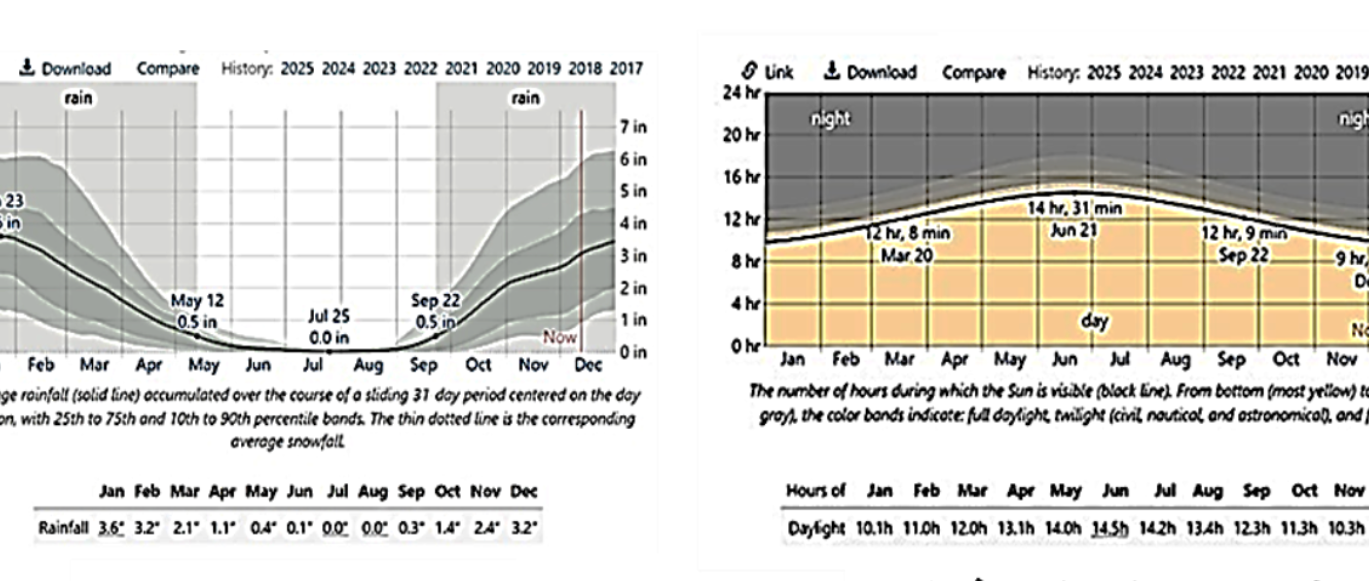

As-Suwayda Governorate, located in southern Syria on the basaltic plateau of Jabal al‑Druze, embodies the profound climatic, economic, and political challenges that many areas of the Middle East are currently facing.

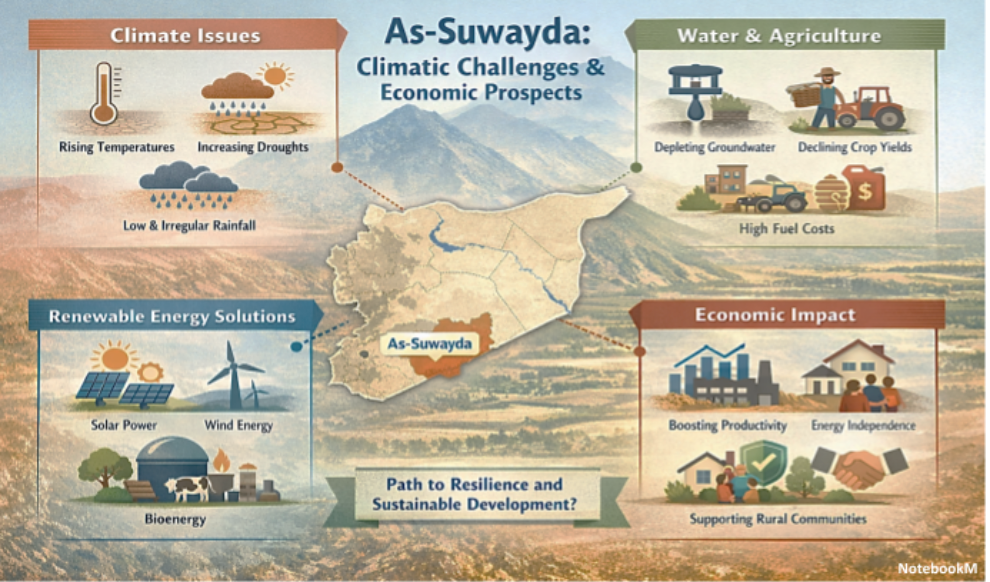

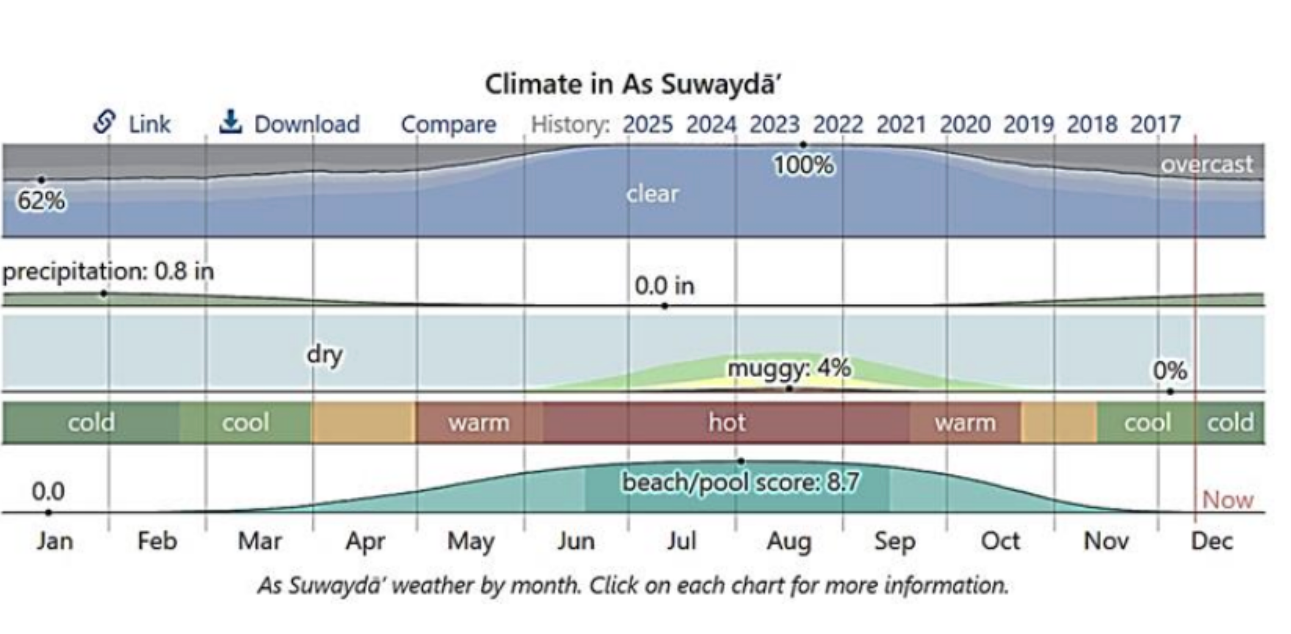

The governorate’s climate is semi‑arid: a hot, dry summer and a cold winter with low rainfall. This defines the local water ecosystem and places strong pressure on agricultural production. The average annual rainfall is only about 300 mm, and precipitation patterns are becoming increasingly irregular. Drought waves have intensified in recent decades.

At the same time, the region is among the areas with the highest annual solar irradiation in Syria. This dual reality—water scarcity and high solar potential—provides a starting point for reassessing development and energy pathways in a region whose livelihoods have traditionally depended heavily on rainfed agriculture (field crops, grapes, and fruits) and livestock production.

The economic situation in As-Suwayda has deteriorated sharply due to the prolonged conflict in Syria, which has damaged infrastructure, reduced energy availability, restricted mobility, disrupted supply routes, and increased fuel costs.

While many households now rely on remittances from abroad, local supply chains – particularly in agriculture, processing, and trade – are under severe pressure.

In this context, energy has become a key factor for economic stability, social resilience, and the population’s ability to maintain essential services.

Power outages, diesel shortages, and the widespread collapse of centralized energy supply systems have severely affected the productivity of rural businesses and increased dependence on generators—raising costs and undermining profitability.

At the same time, the energy crisis has created new investment opportunities. In recent years Syria has witnessed a noticeable shift toward decentralized renewable energy systems, especially in the southern governorates. Households, small businesses, agricultural producers, and local communities are increasingly investing in photovoltaic (PV) systems, battery storage, and sustainable off‑grid solutions.

This development is not only technological; it also reflects a deep societal shift—away from central state institutions toward local self‑reliance, economic independence, and the use of sustainable energy models. For a region like As-Suwayda —characterized by high solar irradiation, relatively stable winds on mountain peaks, and agricultural diversity—expanding renewable energy use opens new horizons for resilience, innovation, and greater economic value from local resources.

Against this background, scientific and practical studies on the interaction between climate, economy, and energy supply in As-Suwayda are of growing importance. A central question is how renewable energy can contribute to stabilizing a conflict‑affected and climate‑stressed region, and to achieving a sustainable transition not only for Syria but also for similar areas in the Middle East and North Africa. The availability of renewables—especially solar, wind, and bioenergy—offers a realistic opportunity to improve access to water and electricity, reduce core production costs in agriculture, increase the economic value of local resources, and create long‑term development prospects.

At the same time, these issues are part of a wider discussion on climate adaptation, energy justice and distribution, socio‑economic participation, and the role of technology under conditions of instability and political crises. This reference review summarizes key findings from selected published scientific research and specialist reports. It highlights how climatic conditions, economic dynamics, technological innovations, and renewable‑energy potential interact to enable scalable sustainable development aligned with local socio‑economic needs and factors.

https://weatherspark.com/y/99245/Average-Weather-in-As-Sawd%C4%81-Syria-Year-Roundالمصدر:

Climate change and local resources in As-Suwayda

Due to its geographic and climatic setting—particularly its semi‑arid climate— As-Suwayda is highly exposed to environmental and economic change. Short rainy seasons, long dry periods, and temperature variability affect agricultural production, the most important economic sector in the area. Most farming is rainfed, while irrigated agriculture is under increasing pressure because pumping costs are rising and groundwater levels are declining.

https://weatherspark.com/y/99245/Average-Weather-in-As-Sawd%C4%81-Syria-Year-Roundالمصدر:

Climate models for southern Bilad al‑Sham (the Levant) project an intensification of these trends: higher average temperatures, more frequent heat waves, longer drought periods, and reduced seasonal rainfall. This makes water scarcity a structural rather than temporary problem, affecting agricultural production, food security, ecosystems, and economic resilience alike (16,17,18,20,25).

In parallel, the political conflict lasting more than a decade has profoundly reshaped social and economic structures. The collapse of central state services—including energy and irrigation infrastructure—has led to sharp fragmentation of local economies and increased reliance on household‑level solutions. Diesel generators, previously a supplementary alternative to the national grid, became a de facto primary electricity source—at high cost, with supply gaps and health risks from emissions.

In this context, renewable energy—especially small‑scale PV systems—has emerged as a vital resource, enabling households, farms, and small enterprises to achieve a degree of self‑sufficiency based on local resources. Decentralization also fosters new forms of local energy economies: communities organize battery storage, farmers install solar‑powered pumps, and small workshops specialize in installing and maintaining PV systems. This occurs largely outside formal state institutions and thus highlights local resilience, autonomy, and sustainable development dynamics (19,23).

International research fields related to climatic aspects and economic prospects in the region

The scientific literature on Syria’s energy system—especially in conflict areas—has grown noticeably in recent years, with increasing attention to renewables in decentralized contexts. However, significant research gaps remain concerning socio‑economic impacts and practical implementation. Current research can be grouped into three areas:

1) Climate and environmental research in the Levant and southern Syria: Many climate studies confirm rising temperatures and increasing drought rates in the Middle East. Long‑term datasets show greater variability in rainfall periods, shorter rainy seasons, and higher frequency and severity of droughts (8,11,22,25). Current scenario modeling for southern Syria projects temperature increases of approximately 2.5–4.0 °C by mid‑century. Mountainous and semi‑arid regions such as As-Suwayda are particularly affected by the concurrence of extreme weather events and groundwater scarcity (1,4,5,7,16).

2) Economic and political studies on Syria’s energy sector: Analyses by international organizations, regional research institutes, and independent experts depict an energy system deeply destabilized by war, destruction, institutional degradation, and politicized resource distribution (1,5,7,12,13). With central power plants, transmission lines, and substations damaged or non‑operational, informal diesel markets, private generator networks, and parallel electricity grids have emerged. Recent studies examine the growing importance of PV systems as an everyday technology for populations that depend heavily on agriculture.

3) Research on renewable energy in conflict settings: Studies suggest that decentralized renewables play a dual role in conflict zones: they reduce dependence on insecure fossil‑fuel (diesel) supply chains while providing access to essential services such as lighting, water pumping, cooling, and communications infrastructure. They are also less vulnerable to sabotage than centralized grids (2,3,6,17,19,21). Nevertheless, only a limited number of context‑specific studies analyze in detail the transformative potential of renewables in southern Syria. In particular, the relationship between solar energy, other local energy sources, and economic and agricultural resilience remains insufficiently studied.

As-Suwayda has a semi‑arid climate with strong seasonal dependence. Summers are long, hot, and almost entirely dry, while winters are relatively cold yet also generally dry. Annual rainfall ranges from about 300 to 330 mm and is concentrated in a few months during winter and early spring. This pattern produces high year‑to‑year variability, increasing the likelihood of crop failure when rains are delayed or absent (10,13,14,15).

Climate change further exacerbates these conditions. Environmental models for the Eastern Mediterranean (e.g., CORDEX-CMIP, CORDEX-CORE, SimCLIM) project an increase in average temperatures (about 2.5–4.0 °C by mid‑century), more frequent extreme weather events, and an additional decrease in seasonal rainfall (22,25).

For agriculture, this implies increased irrigation demand, higher evaporation rates, deteriorating soil moisture, and the approach of many traditional crops—such as wheat, barley, and some fruit species—to their climatic limits, which are crucial for economic returns. This creates a major production challenge (12,13,14).

Water resources and hydrological pressures

As-Suwayda relies heavily on groundwater, as surface water is only seasonally available. Water is mainly extracted from deep wells, often operated with diesel generators. In recent years, associated costs have placed a heavy burden on farmers, and in some cases have led to the abandonment of agricultural investment on those lands.

Key water challenges include:

- Declining groundwater levels due to overuse and lack of regulation.

- High pumping costs due to diesel shortages and price volatility.

- Reduced recharge rates because of lower winter rainfall and higher evaporation.

- Salinization of some aquifers, making irrigation of sensitive crops difficult.

In theory, solar‑powered water pumps can be a decisive solution because they are independent of diesel fuel and deliver maximum performance during periods of high solar irradiation—precisely when plant water needs are greatest.

Agricultural production

Traditionally, As-Suwayda is among Syria’s most fertile regions, thanks to its dark red or yellow volcanic soils rich in minerals. The governorate is known for grapes, fruits, olives, and medicinal herbs, as well as for rainfed cultivation of field crops (such as wheat, barley, and chickpeas).

However, climate change, higher irrigation costs, and political instability have strongly affected productivity and the area of cultivated land.

Main challenges in agricultural production:

- Heat waves reduce yields and quality.

- Water scarcity increases dependence on expensive pumping.

- Rural out‑migration and labor shortages due to conflict weaken farming operations.

- Unstable electricity supply complicates cooling, processing, and storage.

- Insufficient investment in modern irrigation systems (drip, sprinkler/misting, automated irrigation networks).

Farms that increasingly rely on solar energy report more stable production costs, greater planning security, and higher independence from official energy markets and the public electricity grid.

Energy demand and the importance of decentralized supply

Energy demand in the region can be divided into three sectors:

Homes: lighting, cooling, communications, and hot water. This sector suffers strongly from power outages.

Agriculture: water pumping, fruit cooling, processing (drying, pressing), and irrigation.

Small enterprises: handicrafts, shops, workshops, and food‑processing facilities.

Given the disruption of the central electricity grid in large parts of Syria, composite energy systems have spread widely, including:

- PV + batteries for households.

- PV + diesel generator for agricultural operations.

Cost savings and improved reliability provided by PV systems are now among the most important drivers of their rapid diffusion.

Renewable‑energy potential in As-Suwayda

- Solar energy:

As-Suwayda is among the areas with the highest solar irradiation in Syria. Solar-resource maps (e.g., Global Solar Atlas) and renewable-resource assessments indicate that southern governorates, including As-Suwayda, have high irradiation levels exceeding 2000 kWh/m² per year, making solar power a technically and economically promising option for electricity generation (2,3,9,11,15,21). Solar energy is a key development resource in three areas:

A) Supplying electricity to households:

- PV systems cover basic needs (lighting, cooling, internet).

- Reduced diesel consumption and costs.

- Improved local capacity to cope with outages.

B) Agricultural use (solar water pumps, processing, cooling):

- Pumps enable irrigation independent of diesel prices.

- Integration with drip irrigation can reduce water use by up to 40%.

- Solar energy is used for efficient drying of medicinal plants, herbs, and fruits.

C) Agrivoltaics (agricultural PV):

- Protects crops from excessive heat and intense direct sunlight.

- Reduces evaporation.

- Dual land use: electricity generation + cultivation.

- Particularly suitable for vineyards, medicinal/aromatic herbs, and ornamental plants.

- Wind energy:

a complement in hybrid systems. The governorate’s location on the western slopes and exposed peaks of the Jabal al‑Druze range brings moderate to strong winds at several sites, creating suitable conditions for wind turbines.

Potential:

- PV‑wind hybrids can stabilize year‑round supply.

- Well-suited for villages and small settlements.

- Wind (in hybrid systems) can contribute more power at night and in winter, compensating for weaker PV performance in these periods.

Constraints:

- Not economically viable in all areas.

- High installation and maintenance requirements.

- Bioenergy:

using organic residues. Agriculture produces substantial organic residues annually (livestock manure, orchard prunings, olive‑press residues). These can be used for:

- Small biogas units (for heating, cooking, and household electricity).

- Drying and converting into compressed fuel with high energy density as an alternative to firewood or charcoal.

- Thermal use in agro‑processing facilities (fruit‑juice plants, drying facilities).

Discussion

Findings from climate and regional research on Syria and southern Syria indicate that As-Suwayda sits within a complex contradiction between climatic pressures and institutional weakness. Climate change acts as a risk multiplier: higher temperatures, more variable rainfall, and water scarcity aggravate shortcomings in existing energy supplies and threaten the population’s economic base—especially agriculture. At the same time, the collapse of centralized energy infrastructure creates a strategic opportunity for transition, giving renewables particular importance (1,2,7,13,16,18,24).

A key conclusion is that decentralized energy forms—especially PV—play a critical role in ensuring energy security for households and farms. Unlike many other conflict regions where energy scarcity is a primary barrier, self‑organized informal energy has become a foundation of local resilience. This shift is not merely technological; it reflects a socio‑economic transformation marked by the growing importance of local networks (6,17,19,23).

Studies also emphasize that As-Suwayda has characteristics that particularly encourage renewables: high solar irradiation, relatively stable wind conditions on mountain peaks, and abundant secondary agricultural products that can be used for bioenergy. These resources enable better integration of energy, water, and agricultural production into systems that enhance local environmental resilience and economic feasibility (2,3,11,15,21).

Nevertheless, major challenges remain. The lack of regulation leads to wide variation in PV installations and insufficient safety standards. Access to high‑quality batteries and inverters is still limited, undermining long‑term system stability. Moreover, investments in wind and bioenergy are currently minimal despite clear potential for hybrid and more stable models. Social inequalities persist: wealthier households can purchase higher‑quality PV systems, while lower‑income residents continue to rely on diesel generators—an additional financial burden under difficult political and economic conditions.

International research on energy provision in conflict settings supports the assumption that sustainable energy should not be postponed until political stabilization, but should be an active element of reconstruction and economic transition during crises (3,6,23,24). As-Suwayda offers a model case in which, despite structural challenges, communities have begun to develop energy autonomy, indirectly strengthening economic and social stability.

Overall, renewables in As-Suwayda represent more than a technical choice: they are a tool for economic diversification and a factor of social cohesion, enabling adaptation and recovery by transforming environmental and economic crises into opportunities for growth and stability.

Conclusions

- Climatic pressures require structural reorientation in the use of agricultural resources. Climate change intensifies water scarcity and threatens traditional agricultural production systems in As-Suwayda. Sustainable development should focus on efficient irrigation, more resilient crops, and integrated systems that improve the joint use of energy and water.

- Renewables based on local environmental resources are a key mechanism for local stabilization and economic recovery, and for achieving a degree of energy self‑sufficiency. PV systems have proven cost‑effective and reliable and can drive social transformation. They provide new opportunities for households and businesses and reduce dependence on volatile diesel prices and unstable electricity networks.

- An integrated energy mix (solar, wind, and bioenergy) offers greater development potential. Solar is the main resource, but hybrid systems—such as PV combined with wind or bioenergy from agricultural residues—can stabilize supply and generate broader added value, which is particularly important in areas affected by seasonal unemployment and weak markets.

References

- Abel, T., & Huber, M. (2020). Climate change and water scarcity in the Levant. Climate Research Journal, 45(3), 210–225.

- Al-Mohamad, A. (2001). Renewable energy resources in Syria. Renewable Energy, 24(3), 365–371.

- Elistratov, V. V., & Ramadan, A. (2018). Energy potential assessment of solar and wind resources in Syria. Journal of Applied Engineering Science, 16(2), 264–272

- FAO. (2018). Syria: Agricultural livelihoods and food security. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- Femia, F.; Werrell, C., (2012). Syria: Climate change, drought and social unrest. Briefer no. 11 Center for Climate and Security, Washington, DC

- GIZ. (2021). Decentralized renewable energy in fragile contexts: Lessons from the MENA region. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit.

- Gleick, P., (2014). Water, drought, climate change, and conflict in Syria. Weather, Climate and Society, 6 (3), pp. 331-340

- https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/syrian-arab-republic/era5-historical

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Syrian-Arab-Republic_GHI_Solar-resource-map_GlobalSolarAtlas_World-Bank-Esmap-Solargis.png

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Suwayda

- https://globalsolaratlas.info/map?r=SYR&c=34.850493,39.041016,7&c=34.520455,36.584472,6

- https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/45a26bb7-168c-497d-b548-cf8120c35580/content. SPECIAL REPORT (2021) FAO Crop and food Supply assessment mission to the Syrian Arab republic.

- https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/b9c4f6d8-4fb8-42bb-a2c9-e018e38b1167/ Counting the cost Agriculture in Syria after six years of crisis.

- https://weatherandclimate.com/syria/as-suwayda/as-suwayda

- https://weatherspark.com/y/99627/Average-Weather-in-As-Suwayda%C4%81%E2%80%99-Syria-Year-Round

- ICARDA. (2019). Dryland agriculture under climate change in West Asia. International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas.

- IEA. (2023). Renewables: Global outlook and regional profiles. International Energy Agency.

- Karam, J. (2016). Climate and its impact on apple and grape cultivation in As-Suwaida Governorate: A study in applied climatology. Master’s thesis, Faculty of Arts, Alexandria University. (1)

- Kattan, A., & Saad, N. (2022). Energy system collapse and informal electricity markets in Syria. Middle East Energy Review, 14(2), 55–78.

- Makhlouf, T. (2017). Environmental and vegetation status in Al‑Dhamna Reserve – As‑Suwayda. Damascus University Journal of Sciences. (2)

- Ramadan, A. & Elistratov, Viktor. (2019). Techno-Economic Evaluation of a Grid-Connected Solar PV Plant in Syria. Applied Solar Energy. 55. 174-188. 10.3103/S0003701X1903006X. (21)

- Salama, N.M., Cai, R. & Tonbol, K. (2023). Assessing SimCLIM climate model accuracy in projecting Southern Levantine basin air temperature trends up to 2100. Sci Rep 13, 19048 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-46286-7

- UNDP. (2022). Solar energy adoption in conflict-affected regions: Case studies from Syria. United Nations Development Programme.

- World Bank. (2020). Syria damage assessment and reconstruction overview. World Bank Group.

- Zittis, G., Almazroui, M., Alpert, P., Ciais, P., Cramer, W., Dahdal, Y., et al. (2022). Climate change and weather extremes in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. Reviews of Geophysics, 60, e2021RG000762. https://doi. org/10.1029/2021RG000762

About the author

Dr. Rada Maria Abou-Ammar is an agricultural engineer and researcher in agricultural biology and a member of the National Committee for Agricultural Scientific Research in Damascus, Syria. She completed her Master’s and PhD research in agricultural biotechnology and molecular sciences within a cooperation framework between the University of Damascus and the European Union. During her PhD studies at Martin Luther University Halle‑Wittenberg, she focused on molecular biology, fungal genetics, and the causes of plant pathogens’ resistance to pesticides. During her work as a research assistant at the Fraunhofer Institute in Leipzig, she gained many years of experience in research and development related to medicinal plants, biological plant protection, and sustainable agriculture.

Swaida Intellectual Digital Magazine 1, 2026, ISSN: 3099-3172 (online)